Dragons in China are nothing like the fire-breathing monsters of Western fairy tales. Here they are friends of farmers, guardians of rivers, symbols of imperial power and lucky omens that appear on roofs, robes and festival streets. For international travelers, understanding the Chinese dragon opens a delightful cultural doorway: it explains why carved dragons crouch on temple ridges, why boats race under painted dragon heads each summer, and why the Year of the Dragon still elicits cheers across the country. This long-form guide walks you through the dragon’s meaning, its many faces, where to see it for yourself, and how to experience dragon culture respectfully and memorably.

History and Origins of the Chinese Dragon

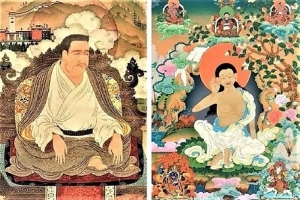

The dragon’s roots in China are ancient and deep. Long before dragons became court symbols, proto-dragon motifs appeared in ritual objects and jade carvings—creatures that combined aspects of snakes, fish and birds. Over millennia the image evolved, absorbing local myths, artistic styles and religious meanings until the dragon became central to the Chinese imagination.

Early myths connect dragons to elemental powers—water, rain and rivers. In agrarian societies, those who could influence rain were credited with ensuring crops and survival. Dragons became natural metaphors for control over water and weather, and that practical association gradually gained spiritual and imperial layers: emperors adopted dragon imagery to signal their authority, and rituals invoked dragons to bless harvests or calm storms.

Mythical Anatomy: Why Chinese Dragons Look the Way They Do

One charming fact about the Chinese dragon is that it is a composite creature—its form borrows pieces from many animals. Traditional descriptions blend the head of a camel, the eyes of a rabbit, horns of a deer, neck of a snake, belly of a clam, scales like a carp, claws of an eagle and paws of a tiger. This patchwork anatomy represents a mythic creature made from the best qualities of the natural world—a being that is at once terrestrial, aquatic and celestial.

That blended form explains why you see dragons used in so many contexts: winding, serpent-like bodies fit river motifs; scaled hides reference fish and water life; strong claws and a fearsome head suggest regal power. The dragon’s visual versatility makes it ideal for murals, roofs, textiles and festival puppets.

Imperial Symbolism and Social Order

For centuries the dragon symbolized imperial authority. Emperors were frequently described as “sons of the dragon,” and dragon motifs appeared on palaces, official robes and carved stelae. Design rules often reflected social hierarchy: certain dragon types or numbers of claws were reserved for imperial use, while lesser nobles and commoners used simplified motifs. The dragon thus served both as a spiritual guardian and a visible badge of rank—an icon of cosmic order mapped onto society.

Types of Dragons: Roles, Habits and Habitats

Chinese tradition knows many dragons, each with distinct roles:

- Spirit Dragons (Shenlong): Weather masters who bring rain and wind. Vital for farming communities.

- Heavenly Dragons (Tianlong): Guardians of celestial palaces and protectors of gods.

- Underworld Dragons (Dilong): Linked to rivers and the earth; often associated with currents and rivers.

- Horned Dragons (Jiaolong): Powerful and sometimes ambivalent figures tied to floods and storms.

- Treasure Dragons (Fucanglong): Keepers of hidden wealth and subterranean riches.

- Coiled or Sea Dragons (Panlong): Dwelling in deep waters, sometimes linked to time and cycles.

- Dragon King (Longwang): The sovereign of watery realms—four directions, four seas in some myths—who rules storms and tides.

Each subtype reflects a different relationship between humans, nature and the divine, which is why dragon imagery can appear both in village rain rites and in imperial palaces.

Dragons by Color: Visual Language and Symbolism

Color matters in dragon imagery. Different hues carry distinct meanings:

- Blue/Green: Often linked to water, spring, and renewal; suggest calm wisdom and nature’s vitality.

- Red: Power, celebration and good fortune—red dragons appear in festivals and parades.

- Yellow/Gold: Imperial and heavenly, evoking nobility, stability and cosmic centrality.

- White: Purity and transformation—used in funerary or more solemn contexts.

- Black: Guardianship of hidden realms or the mysterious balance of forces.

When you see a dragon painted on a temple or woven into a costume, its color is deliberate—an encoded message that complements its position and purpose.

Dragons in Art and Architecture

From imperial palaces to ordinary villages, dragon motifs permeate Chinese visual culture. Look for:

- Roof ridges and eaves: Dragons (or their sons) perch to guard buildings from evil.

- Stone carvings and columns: Dragons wrap columns and framing stones with dynamic movement.

- Porcelain and textiles: Dragons on porcelain vases or embroidered robes signal auspiciousness and status.

- Murals and screens: Dragons frame narratives in temples and palaces, often as cosmic guardians.

The dragon’s flowing form lends itself to architectural choreography: its curves soften angles, its sinuous body transforms static surfaces into vivid storytelling canvases.

Festivals and Public Rituals: Where Dragons Come to Life

To truly experience dragon culture visit during a festival. Two highlights:

- Lunar New Year and Dragon Dances: Elaborate dragon puppets—manipulated by teams of dancers—undulate through streets to drumbeats. The dragon dance is meant to bring prosperity, chase away bad luck and energize communities. Watching a night-time dragon dance, lit by lanterns and punctuated by firecrackers, is a sensory thrill.

- Dragon Boat Festival: Racing boats painted with dragon heads cut through rivers and lakes in dramatic contests of teamwork and speed. The paddling rhythm and festive atmosphere recall ancient myths and communal solidarity.

Beyond these major occasions, local temple fairs and ritual parades also display dragon iconography through smaller processions, incense offerings and neighborhood performances.

The Dragon in Chinese Astrology and Zodiac Culture

As one of the twelve zodiac signs, the Dragon occupies a special place. People born in Dragon years are commonly described as charismatic, confident and ambitious—traits that reflect the dragon’s cultural reputation for strength and good fortune. Dragon years are often seen as auspicious for births and for launching projects, and the personality traits associated with the sign influence everything from gift choices to wedding dates in some communities.

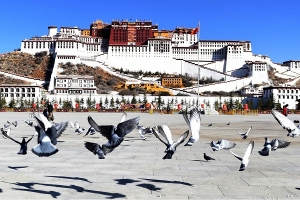

Dragon-Related Tourist Attractions You Can Visit

If you want to see dragons in the flesh (or the stone), plan visits to these kinds of places:

- Ancient palaces and imperial complexes: Carved dragons, painted beams and embroidered robes abound.

- Nine-dragon walls and decorative screens: These walls—often painted with multiple dragons—are striking Instagram-worthy stops.

- Dragon boat festivals in riverside towns: Time your visit to watch races and village celebrations.

- Temples and monastery roofs: Roof ridges are sculptural theaters for dragons and their sons.

- Parks and scenic landscapes named after dragons: Rivers, ridges and terraces often carry dragon-related names and local legends that enrich the landscape.

These sites offer both visual spectacle and cultural context—look for guidebooks or local guides who can explain the symbolism you’re seeing.

Unique Dragon Facts That Delight Travelers

- Composite creature: The mythic anatomy combines many animals into a single idealized form—part camel, part carp, part tiger.

- Nine children: Lore says the dragon had nine sons, each associated with a different decorative or protective role.

- Dragon bones: In rural folklore, “dragon bones” (often fossils) are thought to carry curative or ritual power and occasionally appear in traditional markets.

- Local legends: Many towns boast a “Dragon’s Pool” or “Dragon’s Gate” with stories linking the landscape to dragon deeds—perfect for curious travelers who enjoy folklore.

How to Experience Dragon Culture as a Tourist

Here are practical tips for enjoying dragon culture respectfully and memorably:

- Plan around festivals: If possible, align your trip with Lunar New Year celebrations or the Dragon Boat Festival for peak dragon energy.

- Hire a local guide: Guides can point out subtle features—nine sons tucked under an eave or marker stones that tourists often miss.

- Visit both grand and local sites: Don’t just see the famous palaces—explore neighborhood temples, markets and craft workshops where dragon motifs appear on everyday items.

- Shop mindfully: If you buy dragon-themed souvenirs, consider handcrafted items that support local artisans rather than mass-produced trinkets.

- Learn the symbolism: A basic understanding of color, posture and context will deepen your appreciation of what you see.

Why the Chinese Dragon Endures

The Chinese dragon persists because it is adaptable—part nature, part myth, part state symbol and part local charm. It tells a multitude of stories at once: of human control over rain, of regal authority, of shared folklore and of the enduring relationship between people and place. For travelers, paying attention to dragons unlocks unexpected layers of meaning everywhere you go in China: from a rooftop carving to a village race; from a festival drum to a piece of embroidered silk.

If you want a curated cultural journey that highlights dragon iconography alongside Tibet and the Himalayan fringe, Journey2tibet can craft itineraries mixing iconic dragon sites with regional experiences—temple visits, hands-on craft workshops and festival timing—so you leave with a vivid, well-explained collection of dragon memories.